Forgotten but not gone

Reflections on Illinois Humanities’ Forgotten Illinois 200 program

Lincoln, Douglas, Deere, McCormick, Jane Addams, Reagan, Obama, the Chicago Symphony: a respectable – and only partial – pantheon of Illinoisans known still today to the nation and much of the world.

Yet would Lincoln have become President if not for the masterful campaign management in 1860 by his friend David Davis at the Republican National Convention in Chicago? Would Ronald Reagan have made it in Hollywood and beyond if not for his beloved drama and speech professors at Eureka College? Would today’s CSO be world-famed today if not for its nineteenth-century founder Theodor Thomas?

For the 2018 Illinois Bicentennial, Illinois Humanities supported twenty projects conducted by individuals and organizations throughout the state to dig even deeper and “beneath” the little-known Davises and Thomases, to remember the forgotten, never known, hidden, suppressed, persecuted, slain, even executed, from our state’s history. The grantee-investigators are in the process of unearthing those forgotten, who have been part of the warp and weft of what Illinois has become, of what we are.

As I read through the outlines of these twenty investigations into our past (many still in progress as I write in May 2019), I am roused, by turns, to celebrate, reflect, sigh, become angered, outraged, stimulated. And I find there are lessons here, indeed unearthed and to be built upon, in our efforts to remember the forgotten.

As always with history, the investigators focus on the people and their places, as well as look back upon the natural and built environments that provided their livelihoods and facilitated movement.

We learn that the forgotten struggled, persevered, and often succeeded over trials, tribulation, and danger.

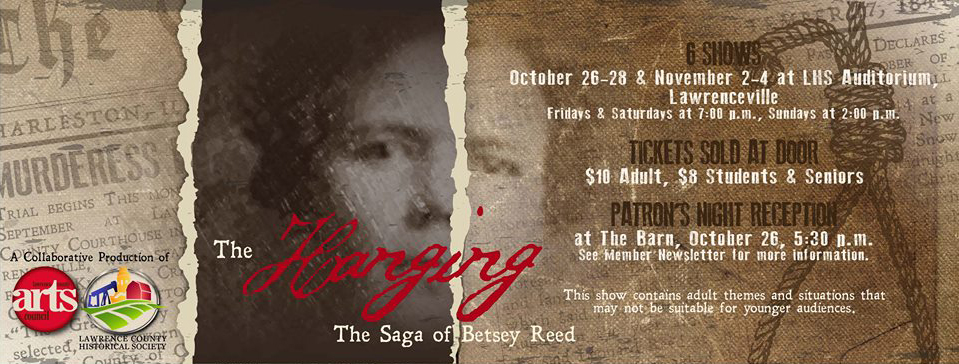

Some, though, didn’t make it. In 1845, in Lawrence County in southeastern Illinois, Elizabeth Reed became the first woman executed in Illinois. Forgotten Illinois 200 investigator Donna Burton uncovered evidence, however, “of a wrongful conviction for a murder she never committed.”

Nor did the free black residents who were captured in Illinois, taken South, and sold again into slavery, make it, so far as we know.

Many of our collective forbears, now forgotten, could have been justifiably proud of their work and ultimate accomplishments in righting such wrongs. Edward Beecher, first president of Illinois College in Jacksonville (and brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe), created the first abolitionist society in our state and stood sentinel against mobs determined to destroy the printing press of Elijah P. Lovejoy at Alton.

Priscilla Baltimore had to buy her own freedom, then that of her husband, before she could establish the village of Brooklyn—an African American community in the St. Louis Metro-East region, which exists today and thrived for several decades in the nineteenth century. Mother Baltimore was also instrumental in the spread and growth of African Methodist Episcopal congregations across Illinois, including Quinn Chapel in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood.

Few today know of the valiant, path-breaking efforts of hundreds, probably thousands, of Illinois women who demanded the vote. In 1912-13, well-to-do white suffrage proponents such as Belle Squires collaborated across racial lines, unusual in the national suffrage movement, with African American activist Ida B. Wells. The Illinois women led courageous protests in Chicago and Washington, D.C., helping propel the Nineteenth Amendment to reality in 1920. Earlier, in 1913, Illinois became the first state east of the Mississippi to grant women the vote, and in 1919 the first state to ratify the amendment.

Almost no one outside the Latino community knew—until scholar and filmmaker Antonio Delgado undertook his Forgotten Illinois 200 project—of the hundreds of Mexican families brought to the Midwest in the early twentieth century to build and maintain the great American railroad network, the foundation of our country’s unmatched economic expansion. They were housed in old railroad boxcars near the tracks, in many small camps along the railroad spines traversing Illinois.

My friend Irene Ponce is the daughter of a man born in “the Davis Camp,” 18 boxcars stripped of their wheels and placed alongside the tracks on the edge of Galesburg. Each boxcar housed one or two, typically large, families. There were five such boxcar camps in or near that city.

According to Irene, the boxcar families in Galesburg were barred from swimming in the public parks, eating at some restaurants, going to dances in town, or trying on clothes in the department stores. The families built their own mini-communities, with chapels in boxcars and baseball teams to play other camp teams in Illinois and Iowa. Untrained yet skillful, compassionate camp-dwelling curanderas cared for their sick and delivered their babies.

Sons of the camps went on to serve with distinction in our armed services in World War II. Today, many descendants still live near the original boxcar camps, prohibited for decades from buying homes elsewhere. Their youngsters have gone on to college and are now leaders in the communities that once repressed them.

Some of the forgotten wanted to be forgotten, or at least hidden, as with both the conductors and the “passengers” on the Underground Railroad. Threading their way along many routes on the Illinois prairie, conductors passed the freed slaves onward at many junctures, ultimately to Canada. Many if not most Illinoisans opposed the work of these abolitionist underground operatives. Indeed, after 1850 the law of the land required citizens to assist in the capture and return of slaves to their masters. Fortunately, few courts of law in Illinois would convict abolitionists charged with evading this grim national law.

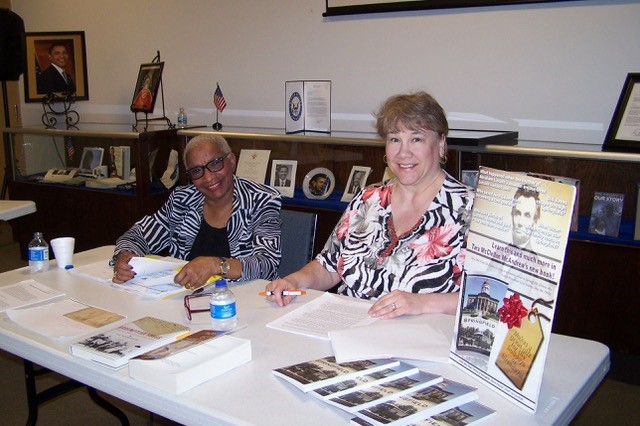

Historical investigator Tara McClellan Andrews is incensed that the history “we know” tells us of Illinois as a free state, as per the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. “But it wasn’t free,” declares Tara! “Humans were bought, sold and willed as property in Illinois, while many lived indentured lives little different from slavery. We need to relearn some of our history,” Tara says. And so we do, via Forgotten Illinois 200.

We learn from her project that the old prejudices Tara found die hard, and slowly. To illustrate, another investigator looked into a particular blot on our state’s history.

In 1919, several young black swimmers on Lake Michigan inadvertently drifted across an invisible line in the water, which separated black from white beach and bathing areas. Stones were thrown at the boys; one died. Thus began the Chicago Race Riots of 1919. For a week, white mobs rampaged through black neighborhoods. Finally, 6,000 National Guard troops quelled the rioting, but not before 23 blacks and 15 whites were killed, and 500 injured. The tragedy hardened and broadened residential segregation in Chicago for decades.

We also learn that the “good guys” of our history were sometimes also arguably the bad guys in the same skin. Bishop Hill storyteller and troubadour Brian “Fox” Ellis has devoted his career to telling the stories of our forgotten and underappreciated. For example, in his Illinois Humanities-supported project, Fox recounts the intertwined, pre-statehood life stories of Ninian Edwards and Potawatomi Chief Gomo.

Prior to statehood, Edwards was our territorial governor. He helped open the prairie to settlers. Yet—and maybe as part of that opening—“his treatment of Indians was part of a failed effort to commit genocide,” says Fox, himself a descendant of the Cherokee.

Edwards’ nemesis Gomo and his Potawatomi warriors were accused of murdering settlers, but can you blame an entire tribe for the behavior of a few rogue men? And the settlers were moving into Indian territory in violation of treaty agreements. Also, Gomo and his men rescued French women and children when American forces burned Peoria in the War of 1812. Fox’s program raises important questions about who is the hero and who is the villain.

So, we learn that our own forgotten are – like the remembered – flawed, inspiring, disappointing, strong, weak, cruel, and compassionate, as people have always been. But we are evolving, if slowly, into better beings overall, says Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker offers persuasive evidence that societies around the world are today less violent than ever, and more tolerant of those with different lifestyles and values.

Part of this may be attributed, I surmise, to having learned from those who came before us that what was glorious in our past worked and that what was dark did not and thus is not to be repeated.

The grantee-investigators of Forgotten Illinois 200 seem driven to fill in the missing pages of our state’s history, to enrich our understanding of what to repeat and build upon and what to reject.

Most of those in our past may be forgotten, but they are not gone. We stand in the midst of our past; the forgotten are part of our bones, part of our behavior.

Storyteller Fox Ellis says the most rewarding feedback he receives from Forgotten Illinois 200 audiences is to hear, “That was fascinating. Now I want to go back into my history.”

Jim Nowlan of Toulon, Illinois, has been a state legislator, state agency director, senior aide to three governors, professor, syndicated columnist, and publisher. Nowlan received B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and is a senior fellow of its Institute of Government and Public Affairs. He has taught courses in American politics at several colleges and universities in Illinois and at Fudan University in China. Nowlan is author or co-author of seven books, including Illinois Politics (2010) and Fixing Illinois (2015). The recipient of numerous awards for contributions to education and civic life in Illinois, he has served as chairperson of the Illinois Executive Ethics Commission and a member of the Illinois Humanities board of directors. Nowlan is president of Stark County Communications, which publishes newspapers in his predominantly rural home county in northwest-central Illinois.